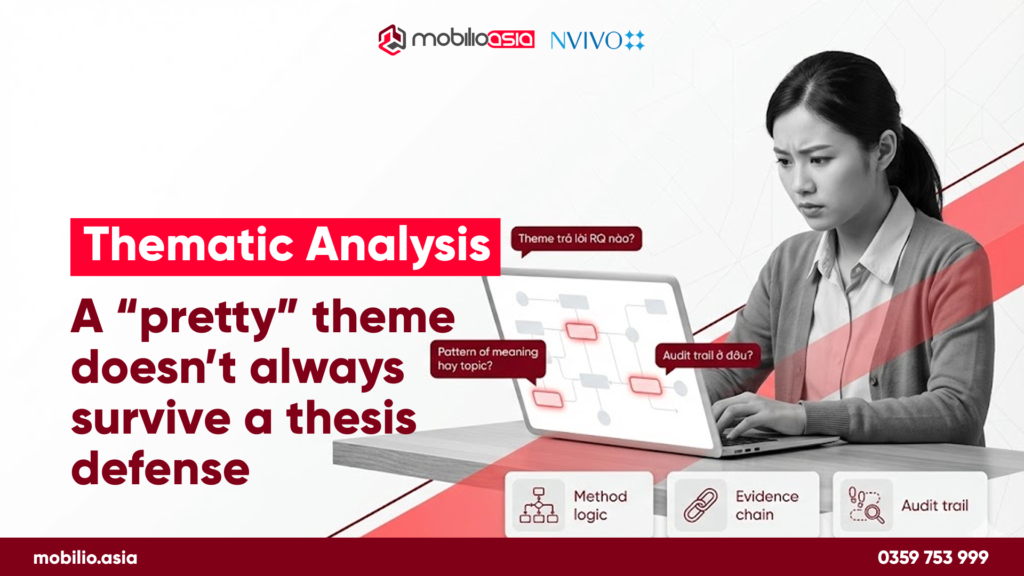

In many pre-defense sessions, you see a familiar paradox. A candidate presents a tidy table of themes, clean labels, a polished thematic map, and a few memorable quotes. But once the Q&A starts, the argument collapses within two or three questions. Supervisors and committee members tend to ask the same things, very directly.

Which research question does this theme answer? Why is this a pattern of meaning rather than a surface topic? How exactly did you move from raw data to codes to themes? What evidence made you choose this interpretation over plausible alternatives?

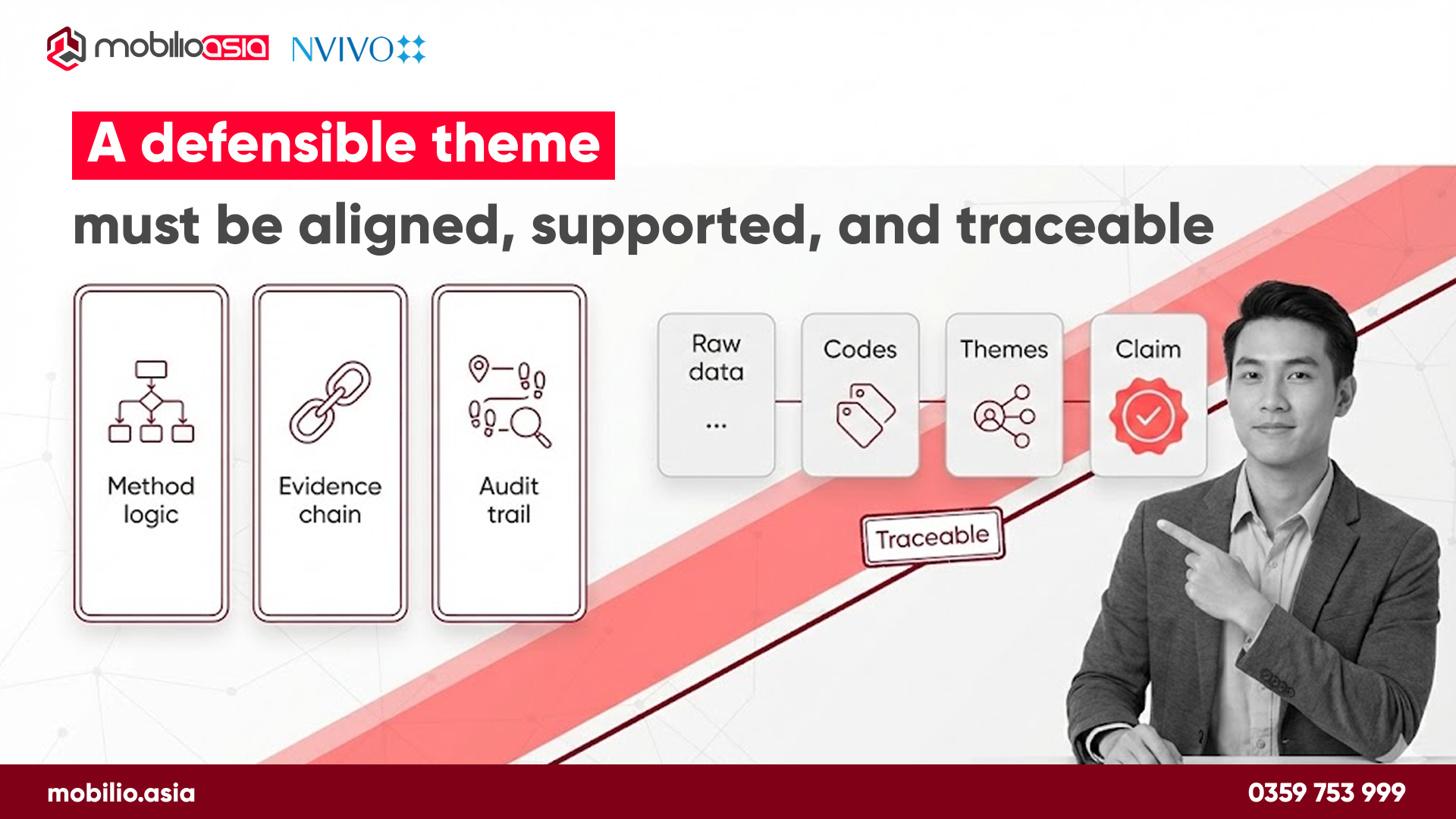

These questions are not meant to trap you. They are the basic checks for whether you are doing qualitative analysis as methodology, or just producing a well-formatted summary. The core idea is simple. A pretty theme is not the same as a defendable theme. A defendable theme stands on three pillars.

First, methodological logic: which version of Thematic Analysis you are doing and what that version expects you to claim and to show. Thematic Analysis is best understood as a family of approaches rather than a single universal recipe, and that “flexibility” comes with a requirement for coherence. See Understanding TA and the foundational article Using thematic analysis in psychology.

Second, an evidence chain: a theme cannot survive on one or two “great quotes”. It needs breadth, variation, and ideally counter-examples that you have actively considered.

Third, an audit trail: you must be able to show your analytic decisions over time, not only your final themes. A practical methodological guide is The Research Audit Trail.

If you want a quick internal primer to calibrate what “meaning” and “interpretation” demand in qualitative work, start with Qualitative Research

1) What Thematic Analysis Means in a Thesis Context

In Vietnamese contexts, “Thematic Analysis” is often translated as “phân tích chủ đề”. The translation is not wrong, but it easily invites a common misunderstanding: treating a theme as a topic label.

In contemporary qualitative methodology, Thematic Analysis is a pattern-based analytic approach that identifies, analyzes, and interprets patterns of meaning across a dataset. The key phrase is patterns of meaning, not topics. A good overview is Understanding TA.

So what is a theme, academically?

In reflexive TA, a theme is commonly conceptualized as a pattern of shared meaning organized around a central organizing concept. This is why many themes look neat but fail under questioning: they are summaries of what participants talked about, not analytic claims about what is going on. See TA FAQs and Doing Reflexive TA.

A useful boundary for thesis writing is this:

If you only group excerpts by “what they are about”, you are doing topic-based organization.

If you can produce a theme statement as a claim, and defend that claim with an evidence chain plus an audit trail, you are doing Thematic Analysis in a defensible way.

The classic reference that established TA as accessible yet theoretically flexible is Braun and Clarke’s paper Using thematic analysis in psychology.

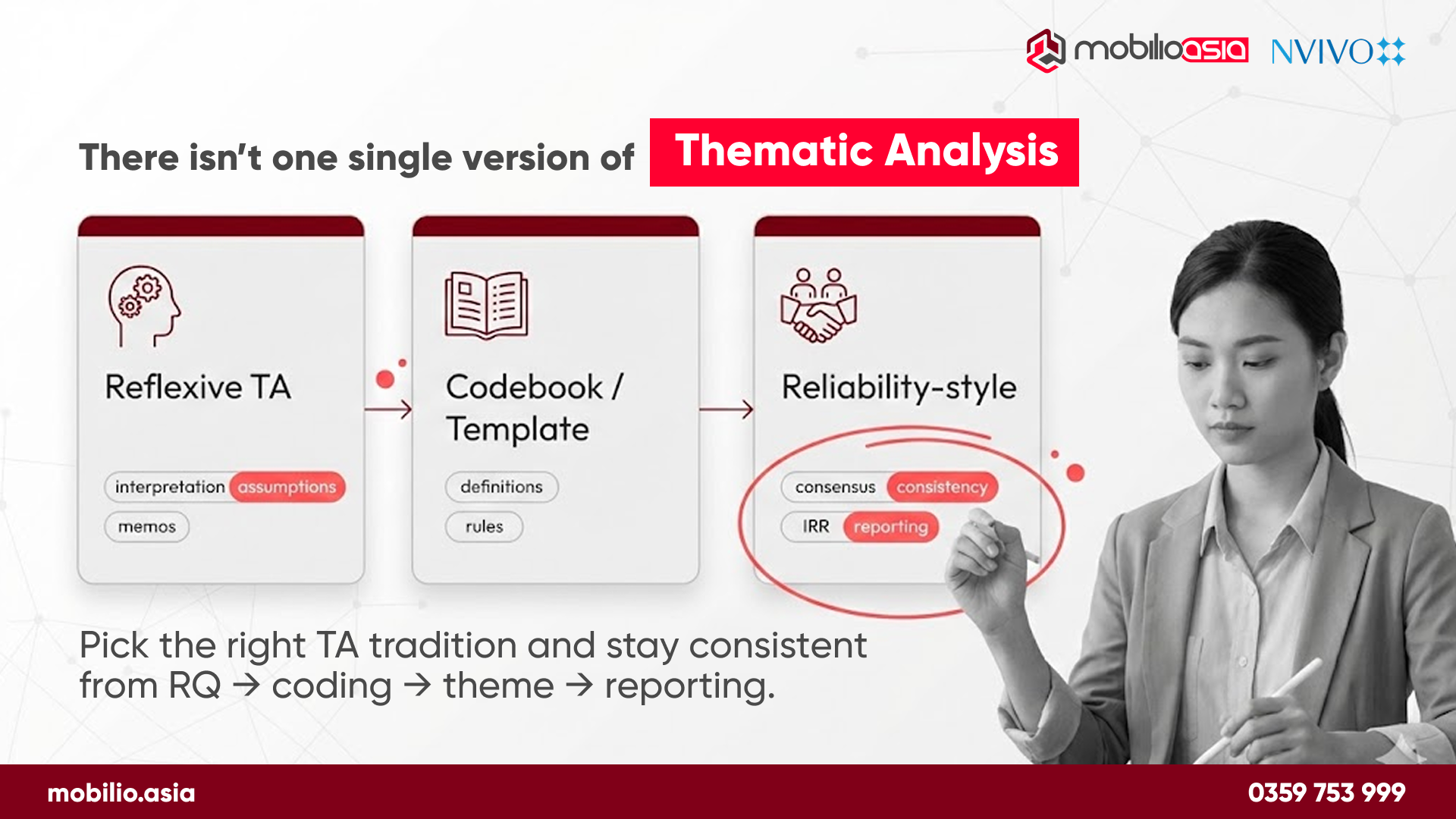

1.2) Thematic Analysis Is Not One Single Method

In the last few years, Braun and Clarke have repeatedly emphasized a practical warning: “I used TA” is not enough. If you do not specify which type of TA, your report can become methodologically incoherent and that is exactly where committees press hardest.

A clear starting point is that TA is an umbrella term, and there are clusters of approaches with different assumptions and different quality criteria. See Understanding TA.

Three commonly encountered orientations are:

Approach 1: Reflexive Thematic Analysis

This approach centers interpretation and reflexivity. The researcher is not a neutral extractor of themes, but an active meaning-maker. As a result, you must be transparent about your epistemological stance, and you must show how your themes were developed through iterative engagement with the data. A reflective overview is Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis.

If you want a detailed worked example that helps you model how to write the analytic narrative and show decisions, read A worked example of reflexive thematic analysis.

Approach 2: Codebook or Template-Oriented Thematic Analysis

Here you often use a more structured coding frame, with definitions, inclusion and exclusion rules, and sometimes team-based coding. This can be highly appropriate for applied projects, collaborative work, or research with clearly bounded questions. A strong open-access overview of template analysis is The Utility of Template Analysis.

Approach 3: Coding Reliability and Post-Positivist-leaning TA

Some approaches emphasize inter-rater agreement, consistency checks, or reliability-like procedures. If you choose this orientation, committees will usually ask detailed questions about the logic of reliability metrics, coder training, disagreement resolution, and whether your procedures actually support interpretive quality.

The central lesson is coherence. If you claim reflexive TA but write as if themes are objective entities “found” in the data, you create a logical mismatch. If you use a codebook approach but do not present code definitions and rules, you invite questions about transparency and auditability.

A very practical resource to self-check quality is Braun and Clarke’s evaluation tool 20 questions to guide your evaluation of a TA paper, based on their quality discussion One size fits all?.

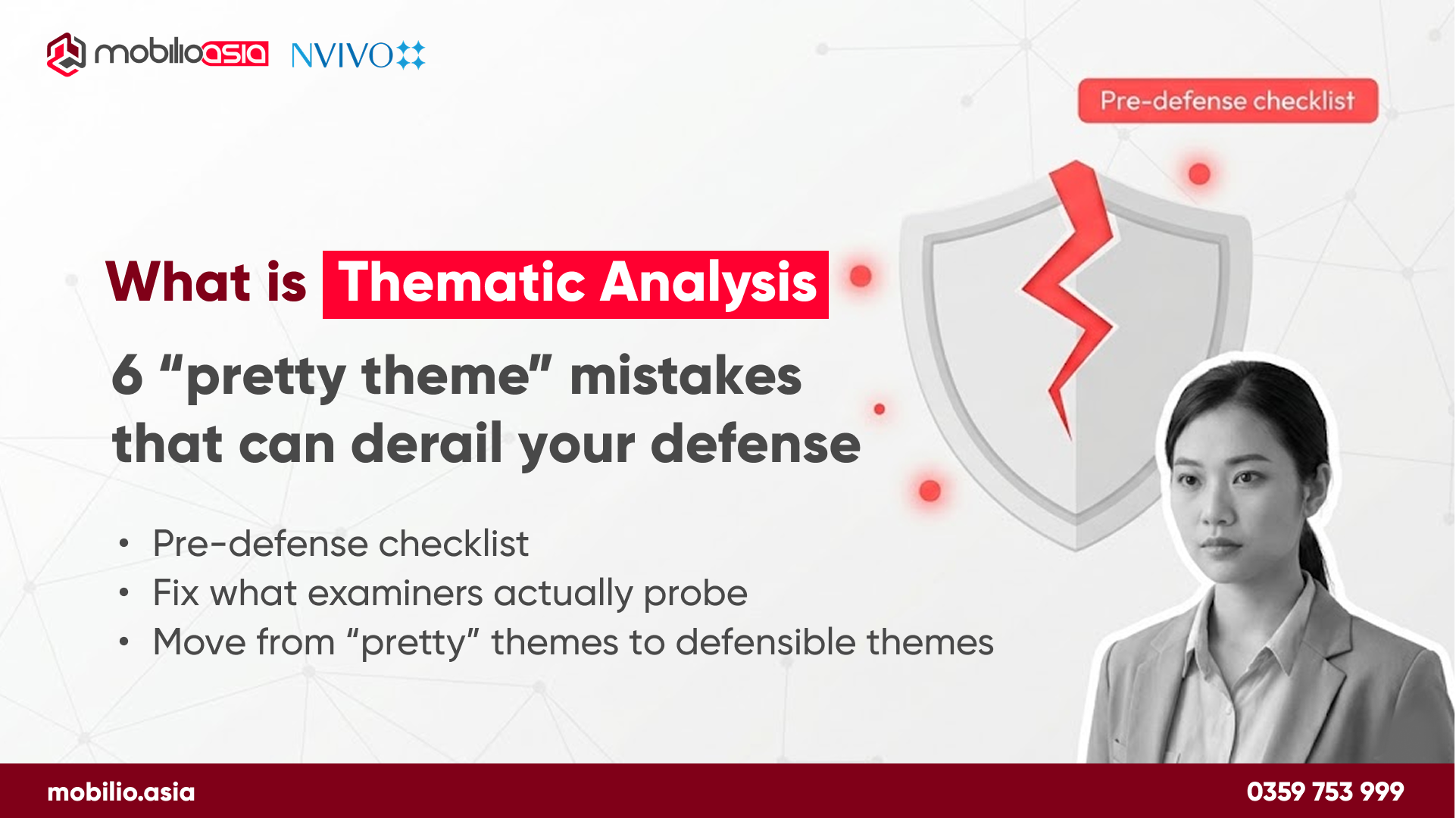

2) Why Pretty Themes Often Fail in a Thesis Defense: 6 Breakpoints

Think of this section as a pre-defense checklist. Each “error” below tends to trigger a predictable committee question.

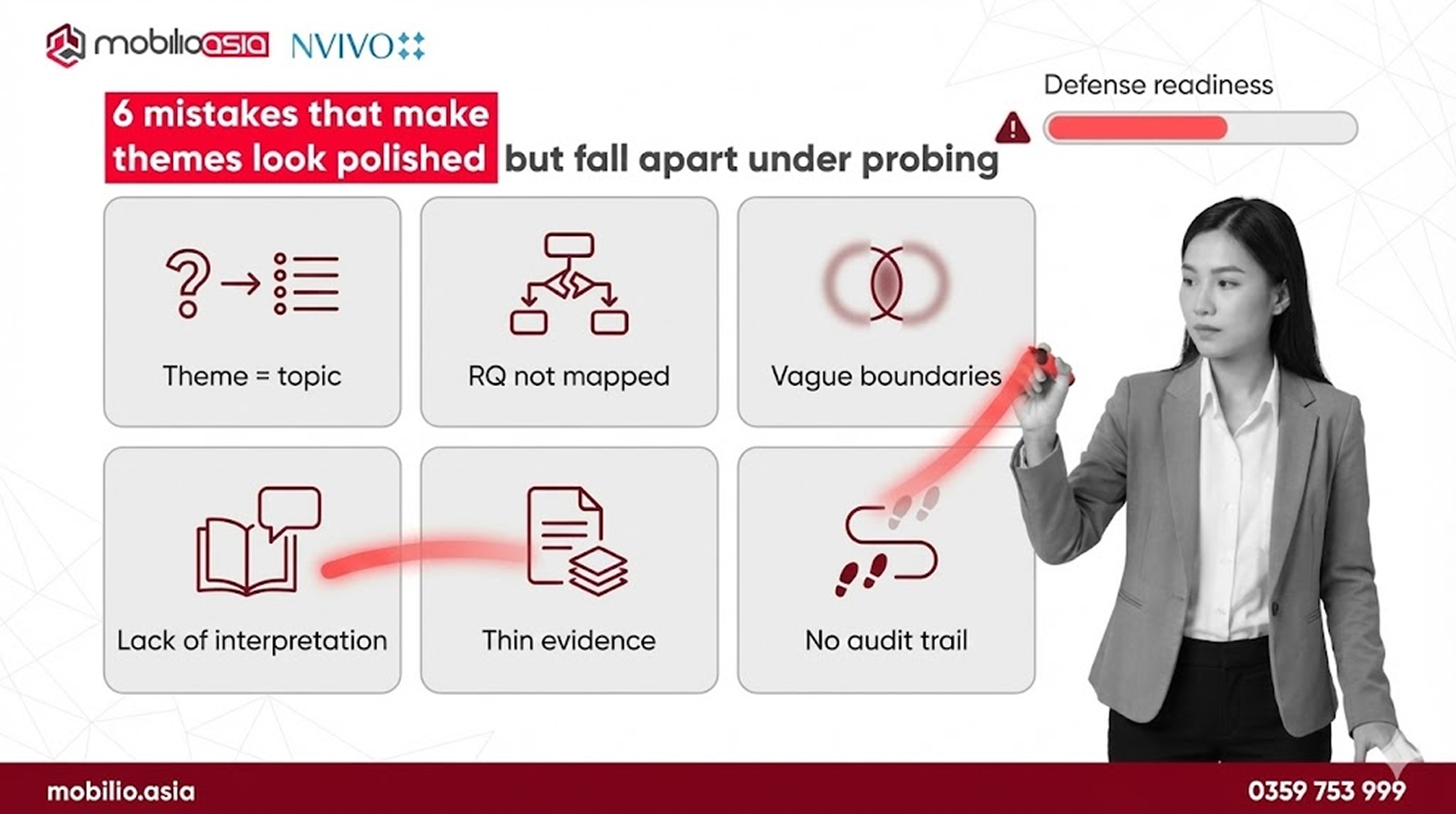

2.1 Mistaking a Theme for a Topic

Symptoms

Your themes are single abstract nouns: pressure, motivation, barriers, support, stress. These labels are not wrong, but they typically signal topic summaries.

Why committees press here

They will ask “How is pressure operating?” If you can only repeat what participants said, you are describing, not analyzing.

How to fix it

Convert topic into claim. Use a structure like:

“X is not only Y, but functions as Z in context B.”

This shift forces you to specify mechanism and meaning, which is aligned with how themes are conceptualized in reflexive TA as patterns organized around a central concept. See TA FAQs.

2.2 Themes Not Locked to the Research Question

Symptoms

Your theme sounds compelling, but you cannot answer “Which RQ does this theme address?” in one direct sentence.

Why committees press here

If a theme does not serve the research question, it becomes “interesting but irrelevant” and your chapter reads like narrative without design alignment.

How to fix it

Map Theme to Sub-question to Evidence Type.

For each theme, write a single line under it: “This theme exists to answer RQ X by showing Y.”

If you cannot write that line, the theme is either underdeveloped or misaligned.

Use 20 questions to guide your evaluation of a TA paper as a structured prompt.

2.3 Themes Without Boundaries: No Inclusion and Exclusion Logic

Symptoms

Your theme becomes a “dumping ground” where almost any excerpt could fit. When asked “Why is this excerpt in Theme A, not Theme B?” you answer based on feeling.

Why committees press here

A theme without boundaries signals weak conceptualization and weak analytic control.

How to fix it

Write a definition plus inclusion and exclusion rules. Even in reflexive TA, you still need to be clear about the scope of your claim and what counts as evidence for it.

This directly supports auditability and makes your defense answers crisp.

2.4 No Interpretive Depth: The “Quote Sandwich” Problem

Symptoms

Your results read like quote, paraphrase, quote, paraphrase. The reader never learns what is analytically at stake.

Why committees press here

They will ask “So what?” and “What is the interpretive contribution?” This is where “pretty” collapses.

How to fix it

Add at least one interpretive layer, such as: mechanism, conditions, consequences.

Then actively seek deviant cases and show how they refine your claim.

The difference between topic summaries and shared-meaning themes is explained sharply in TA FAQs.

2.5 Weak Evidence Chains: Great Quotes, Poor Support

Symptoms

You rely on a small number of vivid quotes and cannot answer “How typical is this?” or “Who does this represent?” or “What does variation look like?”

Why committees press here

They are checking whether your claim is grounded and whether you considered alternative readings.

How to fix it

Separate illustration from demonstration.

Quotes illustrate.

Demonstration comes from showing recurrence, variation, and counter-cases.

If you need language to justify qualitative quality criteria, Tracy’s “big tent” framework is often cited: Qualitative quality: Eight big-tent criteria.

2.6 No Audit Trail: You Cannot Show How Decisions Were Made

Symptoms

You cannot explain why you merged or split themes, renamed them, discarded codes, or selected some excerpts over others.

Why committees press here

Because “why” questions are the heart of a defense. Without an audit trail, your analysis can look like personal opinion.

How to fix it

Maintain a decision log and analytic memos. Track versions of your thematic map. Keep evidence of how your thinking evolved.

A practical guide with a checklist is The Research Audit Trail.

If you want an internal resource that mirrors common qualitative analysis pitfalls, see 3 Qualitative Data Analysis Mistakes.

3) What a Defendable Theme Looks Like

A defendable theme is not the prettiest label. It is the clearest claim with the strongest support.

Here are five criteria you can use as a defense-ready standard.

3.1 Five Criteria for Defense-Ready Themes

Aligned

The theme directly addresses your RQ and matches the TA approach you claim to use. Quality practice emphasizes coherence between methods and reporting. See One size fits all?.

Distinct

The theme has boundaries and does not blur into other themes. Use definitions and rules.

Supported

The theme is supported by a wide evidence range, including variation and deviant cases, not only best quotes.

Insightful

The theme interprets meaning and mechanism, not just content. It answers “what is going on here?”

Traceable

You can trace how the claim emerged from data through coding and theme development, supported by an audit trail. See The Research Audit Trail.

3.2 A Strong Theme Statement Template

A strong theme statement is usually 1 to 2 sentences with three parts:

Claim: what pattern of meaning and what central concept

Context: where and under what conditions it operates

Implication: why it matters for your RQ and argument

Example:

“Evaluation pressure functions as a self-censorship mechanism, pushing postgraduate students to prioritize formal safety over academic risk-taking, weakening their ability to defend the logic of their claims.”

This is defendable because it states a mechanism, a context, and an implication. It gives you something to prove, not just to present.

4) A Thematic Analysis Process That Holds Up in a Defense

Committees do not need every notebook you ever wrote. But they do need to see that you worked with a rigorous, coherent process.

A practical and widely used process is the iterative six-phase framing described in Doing Reflexive TA, paired with the classic overview Using thematic analysis in psychology.

4.1 Start With Positioning, Not Coding

Before coding, write a short reflexivity note.

Are you insider or outsider

How might your position shape interpretation

Are you aiming for semantic themes or more latent interpretation

These decisions determine what kind of claim you can responsibly make. This connects to coherence expectations discussed in Understanding TA.

4.2 Move From Descriptive Codes to Interpretive Codes

Early coding can be descriptive for coverage. But to build themes that defend, you need interpretive codes that express action, function, or mechanism.

Descriptive: “pressure”

Interpretive: “self-censoring to avoid evaluation risk”

Use in vivo codes selectively, only when the phrase captures analytic meaning, not just memorable wording.

4.3 Build Themes by Shared Meaning, Not Shared Keywords

Two excerpts can share the word “pressure” but express different meanings. Group by the central organizing concept, not vocabulary. This distinction is explained in TA FAQs.

For ambiguous excerpts, do one of two things:

Assign it to the theme that best fits your claim and record why in a memo

Or use it deliberately to discuss overlap and tension, but still explain your rationale

4.4 Review Themes With Two Logics

Internal logic: does the theme tell one coherent story

Global logic: do all themes together answer the RQ without gaps

Document changes. Version your thematic map. This is where your audit trail becomes your defense shield. See The Research Audit Trail.

4.5 Write Results as Argument, Not as Scrapbook

A strong TA results section follows a rhythm:

Theme statement as claim

Evidence clusters showing recurrence and variation

One deviant case and what it changes in the claim

Connection to literature and implications for the RQ

If your thesis is mixed methods, you should also explicitly integrate. Integration principles and practices are summarized in Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs, and joint displays are a practical reporting tool described in Joint Displays.

For an internal reference on mixed methods positioning, you can link readers to Mixed Methods Research.

5) Defense Questions You Should Rehearse

These are the questions that commonly expose “pretty but fragile” themes.

Methodology and fit

Why is Thematic Analysis appropriate for your RQ

Which type of TA are you using and what does that commit you to

How do your epistemological assumptions match your analysis

Use Understanding TA to justify the “family of approaches” logic, and 20 questions as a rehearsal checklist.

Quality and rigor

How did you ensure credibility and coherence

How did you handle deviant cases

How can someone follow your analytic decisions

You can ground “auditability” using The Research Audit Trail and qualitative quality language via Eight big-tent criteria.

Evidence and interpretation

How representative is this excerpt

Why is this pattern significant

Why not another interpretation

Theme boundaries

How is Theme A different from Theme B

Why did you merge or split themes

What is the central organizing concept of each theme

The boundary and central concept discussion is especially clear in TA FAQs.

6) A Quick Pre-Defense Checklist (12 Questions)

1 Can I state what RQ this theme answers in one sentence

2 Do I have a clear central organizing concept

3 Do I have inclusion and exclusion rules, even informally

4 Do I show recurrence and variation, not only vivid quotes

5 Do I include at least one deviant case per major theme

6 Can I explain why alternative interpretations are less persuasive

7 Can I trace raw data to codes to theme

8 Do I have memos and a decision log for major changes

9 Does my write-up match the type of TA I claim

10 Are themes distinct yet collectively coherent

11 If one theme is removed, does the argument still answer the RQ

12 Would another researcher understand my analytic decisions from my audit trail

If you want a structured quality lens, use 20 questions.

Conclusion

Thematic Analysis is not hard because the steps are complex. It is hard because it demands disciplined argumentation. If you treat each theme as a claim that must withstand criticism, you naturally do three things that make your defense stronger: you clarify your TA approach, you build evidence chains with variation and counter-cases, and you maintain an audit trail that makes your reasoning visible.

If your project includes quantitative components or a mixed methods design, tools can help you manage data, references, analysis transparency, and integration.

Here are common tools postgraduate researchers use in mixed workflows:

NVivo for qualitative data management, coding, memos, and audit trail practices

Citavi for literature and reference management

XLSTAT for statistical analysis inside Excel

EViews for econometrics and time series modeling

SmartPLS for PLS-SEM modeling

Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt