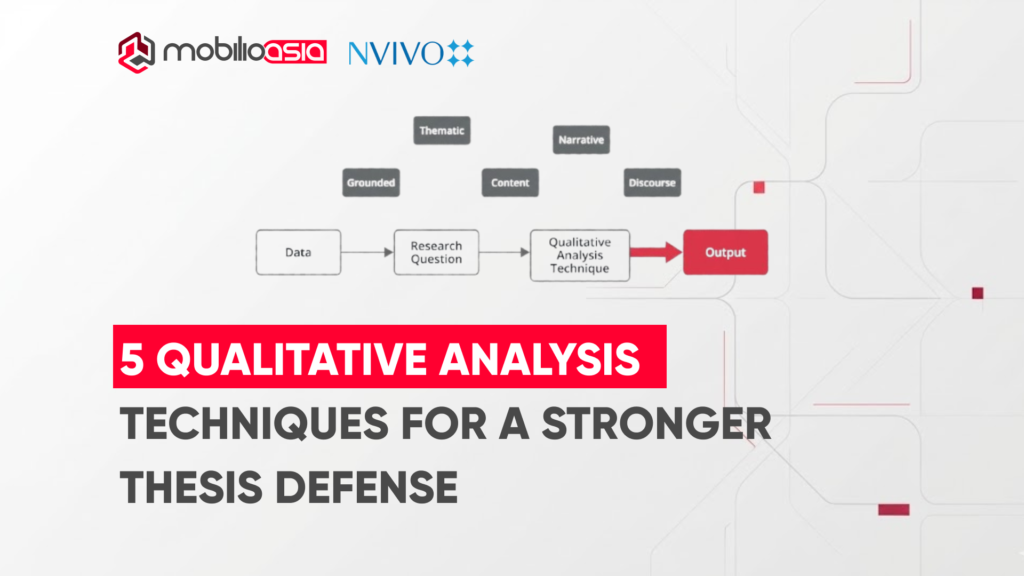

Graduate-level qualitative data is rarely the real problem. Interviews can be well designed, open-ended questions can be clear, and sample size can be acceptable. Yet many theses still get feedback like “weak analysis,” “unconvincing argument,” or “doesn’t answer the research question.” In most cases, the weakness is not the data it’s the analysis decision, especially the mismatch between the research question, the qualitative analysis techniques, and how findings are interpreted.

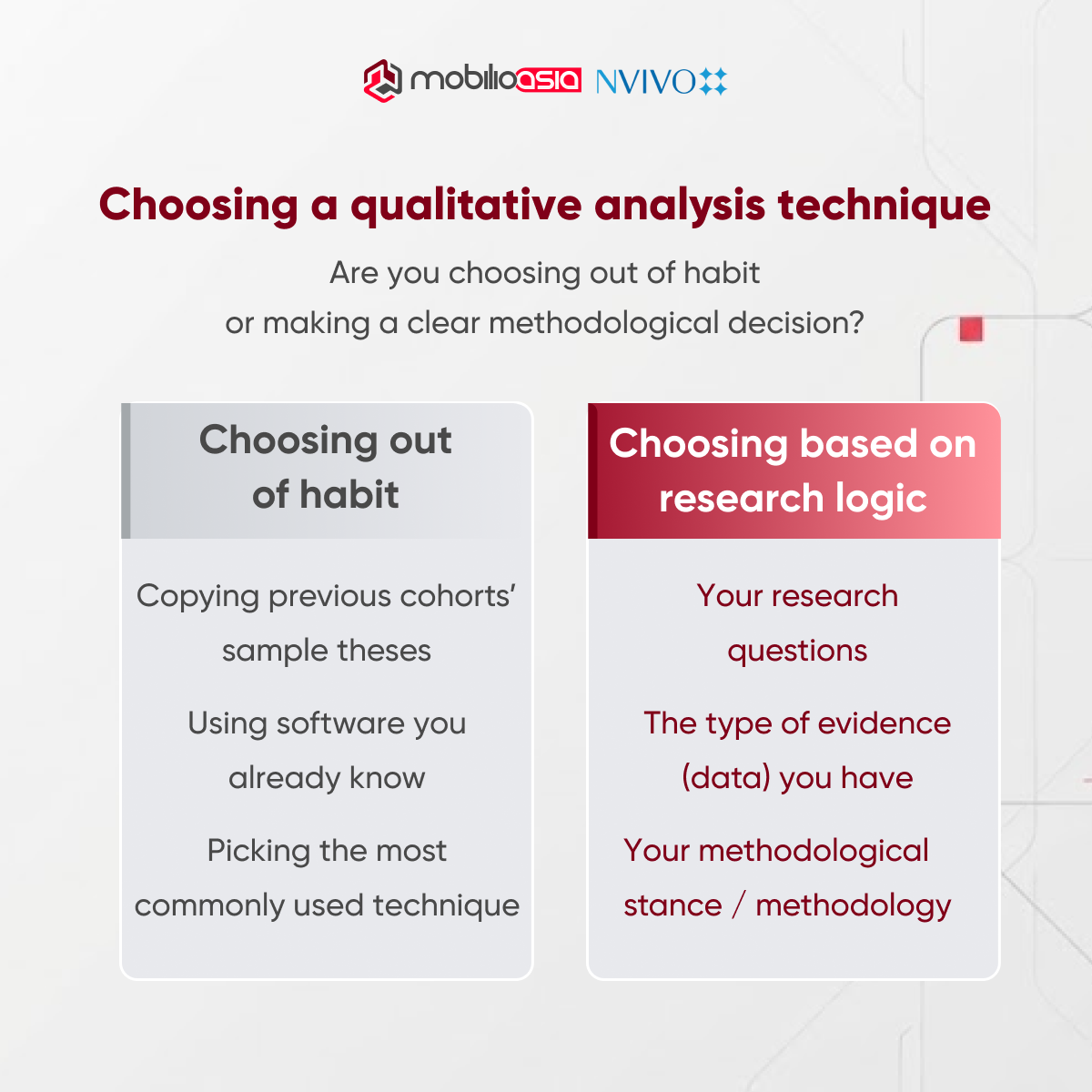

A common pattern is choosing qualitative analysis techniques by habit: copying an older cohort’s template, following whatever the software supports, or picking a method simply because it is “popular.” These choices may look correct on the surface, but they often lack methodological justification in the specific context of your study.

In foundational qualitative methodology, “how you analyze” is part of research design and must align with your research question and the kind of evidence you aim to produce (read more Creswell & Poth (2018)). From that perspective, Thematic Analysis, Grounded Theory, Content Analysis, Narrative Analysis, and Discourse Analysis are not just tools, they are methodological choices with clear trade-offs and limits.

In thesis defenses, committees rarely ask: “Which qualitative technique did you use?” More often they ask: “Why is this technique appropriate for your research question?” If you can’t answer that clearly, your entire analysis can feel fragile even if your procedure looks “standard.”

This post is a decision guide to help graduate students treat qualitative analysis techniques not as a final technical step, but as a methodological choice that shapes your evidence, your argument, and the strength of your conclusions.

Read the companion piece: 3 qualitative analysis mistakes

Qualitative analysis techniques are methodological decisions, not technical steps

In graduate theses, qualitative analysis techniques are not merely about “processing” data after collection. They determine what counts as evidence, how claims are built, and how data connects to conclusions. The same dataset can yield very different results depending on the analytic approach because each technique creates a different pathway of academic argumentation.

This is why a “wrong” technique is often not wrong in form. You can describe coding steps properly, use software correctly, and write a neat Methods section. But if the technique does not fit the research question, you get a mismatch between data, analysis, and conclusions, one of the fastest ways to receive “weak analysis” feedback.

If you want a quick conceptual anchor for “logic of inquiry” in qualitative design, see Creswell & Poth (2018).

1) Qualitative analysis techniques for patterns: Thematic Analysis

Good for synthesizing shared meanings; not ideal for explaining mechanisms

Thematic Analysis is widely used in graduate theses, especially with interviews and focus groups. Its core strength is identifying and organizing recurring meaning patterns in the data (read more Braun & Clarke (2021)).

When to use it

Use Thematic Analysis when your research question focuses on:

- participants’ experiences

- perceptions and interpretations of a phenomenon

- attitudes, viewpoints, or evaluations

In these cases, the goal is not to build a causal model, but to generate defensible themes that reflect how participants make sense of the topic.

When not to use it

Avoid relying on Thematic Analysis when your question requires:

- explaining a process (how something develops over time)

- identifying causal pathways or mechanisms

Themes can describe what is happening, but often cannot explain why or how it happens without additional analytic commitments.

A common risk

A common warning sign is “themes that sound reasonable” but do not directly answer the research question. Braun & Clarke caution against surface-level themes when the analysis stays descriptive rather than analytical (read more Braun & Clarke (2021)).

2) Qualitative analysis techniques for theory-building: Grounded Theory

Good for generating theory; not suitable when your design is fixed

Grounded Theory is a high-commitment approach used when your goal is not only to summarize themes, but to develop a theory or explanatory model grounded in data. It typically requires analysis and data collection to proceed iteratively (read more Charmaz (2014)).

When to use it

Use Grounded Theory when you aim to:

- develop a new theoretical model or framework from empirical data

- explain a social process or mechanism through emerging concepts

When not to use it

Avoid Grounded Theory when:

- your proposal has a tightly fixed scope that cannot shift

- your research question cannot be adjusted as concepts emerge

- your dataset is already complete and cannot be expanded

In these cases, Grounded Theory often becomes a label rather than a method.

A serious mistake to avoid

A common high-risk issue is claiming Grounded Theory in Methods without showing the corresponding logic: open coding, axial/selective coding (depending on tradition), and constant comparison. Without these, the method can become an easy target in defense (read more Charmaz (2014)).

3) Qualitative analysis techniques for large text datasets: Content Analysis

Good for systematic organization; not ideal for deep meaning-making

Content Analysis is often used when you have a substantial amount of textual material and you need a systematic approach to organizing, categorizing, and comparing content. A key reference is Krippendorff (2018).

When to use it

Use Content Analysis for:

- policy documents, reports, media, organizational materials

- secondary documents and archives

- open-ended survey responses

It is especially useful when your study needs consistent comparison across groups, time periods, or contexts.

When not to use it

Avoid Content Analysis when your question is centered on:

- subjective meaning and personal interpretation

- how participants construct meaning from lived experience

Counting categories or frequencies often won’t capture depth.

A common risk

A typical risk is results that look “rigorous” (tables, percentages, structured categories) but lack interpretive argument. If your analysis stops at “what appears more,” without explaining “what it means for the research question,” it can be judged as descriptive or pseudo-quantitative (read more Krippendorff (2018)).

4) Qualitative analysis techniques for lived stories: Narrative Analysis

Good for individual experience over time; not designed for generalization

Narrative Analysis focuses on how people construct meaning through stories—structure, sequencing, emphasis, and interpretation. It treats the story as a whole unit rather than fragmenting it into codes or themes (read more Riessman (2008)).

When to use it

Use Narrative Analysis for research about:

- life stories and turning points

- personal decision-making journeys

- learning trajectories, identity shifts, role transitions

The aim is depth, not frequency.

When not to use it

Avoid Narrative Analysis when your study requires:

- comparisons across many participants

- generalized conclusions across groups

It’s not designed for aggregating many narratives into one broad claim.

A common risk

A frequent risk is a thesis that becomes “storytelling” rather than analysis. The data may be rich, but without explicit analytic logic, committees can view it as descriptive retelling. Riessman emphasizes analytic work beyond narration (read more Riessman (2008)).

5) Qualitative analysis techniques for language and power: Discourse Analysis

Good when language is the object; not a “supporting add-on”

Discourse Analysis treats language as the central object of study not just a channel for information. It examines how discourse is constructed and reproduced across contexts such as academia, policy, and institutions (read more Gee (2014)).

When to use it

Use Discourse Analysis for topics involving:

- academic discourse and disciplinary language

- policy language and governance texts

- media discourse, public statements, organizational messaging

It helps analyze how language shapes meaning, legitimacy, and power.

When not to use it

Avoid Discourse Analysis if your research question is about:

- behavior, attitudes, or experience without analyzing language structure and function

If language isn’t central, the method will feel misaligned.

A common risk

A major risk is analysis becoming too abstract especially when committees are not trained in discourse traditions. If you don’t clearly define theory, unit of analysis, and analytic logic, the work can be judged “hard to follow” or weakly connected to your research aims (read more Gee (2014)).

Comparison table: qualitative analysis techniques by research goal and methodological limits

Figure X summarizes the relationship between your core research goal, the qualitative analysis techniques that fit that goal, the type of academic argument each technique supports, and the methodological limits/risks you should anticipate.

This table is designed as a decision aid, so you choose a technique based on research logic and the argument you need to produce, not on habit or whichever tool you already know.

| Core research goal | Qualitative analysis technique | Type of academic argument it produces | Methodological limits & typical risks |

| Synthesizing shared meaning patterns across participants | Thematic Analysis | Theme-based argumentation: clarifies similarities and differences in experiences across participants | Can stop at description if analytic work is weak; themes often cannot explain mechanisms or processes on their own |

| Developing a new theoretical framework or model from data | Grounded Theory | Theory-building argumentation: explains processes and relationships between emerging concepts | May fail to generate “theory” without theoretical sampling or when the design is not flexible/iterative |

| Systematizing and comparing large-scale qualitative text data | Content Analysis | Category-and-comparison argumentation: organizes content into categories and compares patterns/trends across sources | Can become surface-level counting; results may look rigorous but lack interpretive depth |

| Analyzing individual experience over time | Narrative Analysis | Narrative-structure argumentation: explains how individuals construct meaning through story structure and sequence | Hard to generalize; theses may drift into storytelling rather than analysis |

| Analyzing how language constructs meaning and power | Discourse Analysis | Discourse-based argumentation: focuses on language, structure, and social context to show how meaning and legitimacy are produced | Can become too abstract; difficult to defend if the committee is not discourse-trained or if units/theory/logic are unclear |

How to read the comparison table

This table is not meant to identify the “best” method. Instead, it highlights the methodological trade-offs that come with different qualitative analysis techniques. Your selection should be based on:

- your actual research goal (description vs explanation vs theory-building),

- the type of academic argument you need to produce, and

- the methodological limits you are willing and able to justify in your thesis defense.

In other words, choosing qualitative analysis techniques is choosing a way of arguing, not just a way of processing data.

Conclusion: choosing qualitative analysis techniques is choosing how you will defend your thesis

At master’s and doctoral levels, committees evaluate more than “correct procedure.” They evaluate the logic behind your analytic choices. Even a well-executed process can produce weak argumentation if the technique doesn’t fit the research question.

That’s why qualitative analysis techniques should never be chosen “just to finish analysis.” Each technique carries assumptions, limits, and a distinct kind of evidence. Choosing a technique is choosing what you can legitimately claim and what you can defend under critique.

Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt